Sirius – a Mess of Potash

- – an ‘In My View’ article – by Nigel Ward

~

It would seem to me that no regulatory statute or Act of Parliament should be considered to be beyond the scope of amendment – ‘written in stone’.

It is to be hoped that every Act to receive the Royal Assent has achieved that status only following a most robust debate. Its precise terms must satisfy a majority in two Houses of Parliament. I do not suggest for one moment that MPs and Peers of the Realm are infallible. Verily not.

Nevertheless, if we are to accept the concept of democratic government, we must embrace (with a measure of trust) the fact that our democratic process has, with each new Act of Parliament, delivered unto us a new piece of legislation genuinely believed, by a majority, to best serve the interests of the populace – not only in the present moment when the Act becomes law, but for the foreseeable future.

How long is ‘the foreseeable future’?

That must surely be a matter of context.

Consider the following entirely fictional examples:

- “Following unprecedented heavy rain, there will be no racing at Redcar for the foreseeable future.”

- “The Prime Minister stated that, owing to the prevailing economic circumstances, Britain’s plans for colonising the Antarctic have had to be shelved for the foreseeable future.”

- “As a result of the nuclear attacks on all of the worlds major oil production hubs, there will be no petrol or diesel available for civilian motor or rail transport in the UK for the foreseeable future.”

Loosely speaking, we can imagine that these three fictional examples have used the phrase ‘for the foreseeable future’ to indicate, respectively, periods of time varying from several months, to several years, to several decades. I need not go on.

Beyond the scope of these examples, we should consider the case of law-making the very nature of which requires it to take an even longer view – perhaps even an infinite and immutable view. The example of Isaac Asimov’s ‘Three Laws’ (of Robotics) comes readily to mind:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

These (fictional) ‘laws’ are entirely lucid and comprehensible. One may play around with the precise form of words, but fundamentally they are grounded in the accepted notion of the supremacy of man, intellectually and morally, over his own creations – however humanoid they may appear to be.

With all of this firmly in mind, let us now turn our attention to the National Parks & Access to the Countryside Act of 1949, which the National Parks website informs us was enacted in pursuance of two statutory purposes – with a caveat. I quote:

The Environment Act 1995 revised the original legislation and set out two statutory purposes for National Parks in England and Wales:

- Conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage

- Promote opportunities for the understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of National Parks by the Public

When National Parks carry out these purposes they also have the duty to:

-

Seek to foster the economic and social well being of local communities within the National Parks

It may be that there are those who disagree with the two stated objectives. Their avenue of recourse must be to lobby MPs in an effort to abolish or amend the National Parks & Access to the Countryside the Act.

For the rest of us, it is a measure of our cultural advancement that we now recognise the irretrievable preciousness of our surroundings and that they are beyond the compensation of mere material reward.

I take the view that nothing has passed since the ratification of the National Parks & Access to the Countryside Act that militates in favour of the belief that the ‘foreseeable future’, as envisaged in the late 1940s, has now expired and a new exploitative ethos should be the order of the day.

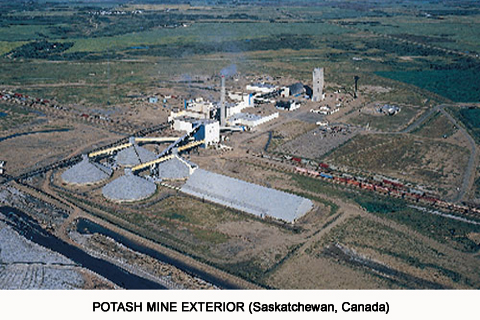

I am here reminded of the words of the celebrated Sioux chief, Sitting Bull in 1877, in (of all places) Saskatchewan (where things have not been going so well in the mining industry of late):

- “The love of possessions is a disease with them. They take tithes from the poor and weak to support the rich who rule. They claim this mother of ours, the Earth, for their own and fence their neighbours away. If (North) America had been twice the size it is, there still would not have been enough; the Indian would still have been dispossessed.”

I do not wish to be dispossessed of even one square metre of our National Park.

So it is that rather slippery caveat that must now come under closer scrutiny. Let me repeat it, for convenience – and emphasis:

- Seek to foster the economic and social well being of local communities within the National Parks

Without entering into a semantic analysis of the terms of the Act itself, I hope we can agree on the fact that Parliament, having recognised the irrefutable social importance of our environment, our landscape and our habitat, has enshrined the inviolable sanctity of our National Parks precisely because, though the land that embodies them may lie in private ownership, the collective vista, the sense of place, of the North Yorkshire Moors National Park belongs to us all – or, rather, we belong to it.

In simple terms, that quality that is so precious to us in the very nature of the National Park is not divisible into separate ‘lots’, subject to private ownership, to be disposed of at the landowners’ pleasure; it is something greater in the whole than in the sum of its parts.

So this caveat of the ‘economic and social well being’ requires very careful inspection indeed.

Technological developments in the area of genetic modification of crops, livestock and even humans are provoking ethical debates that are scarcely able to encapsulate the precise nature of such revolutionary developments, even within the coming months, never mind decades or generations stretching unto the conclusion of mankind’s tenure on this planet.

But that does not mean that such developments must escape regulation; far from it. Clearly, in matters of profound importance to the populace, measures must be taken which not only include within them a flexibility for future amendment (in the light of as-yet unforeseen changes of circumstance), but also safeguards against those who would seek to claim that those unforeseen circumstance are now already upon us, and the fundamental principles of the National Park & Access to the Countryside Acts must be diluted or disregarded to facilitate the pursuit of a private agenda – profit. Personal gain.

I think we already knew, despite protestations to the contrary, that the prime and indeed sole private agenda of those who support the York Potash project is precisely that – personal gain – however much they protest that it is genuinely and sincerely pure altruism in service of the greatest good for the greatest number – the land-owners, the job-seekers and whoever else.

Even the most avaricious of the Sirius hangers-on club cannot credibly deny that. And even they would not contend that the globe-trotting Chris Frazer has munificently descended upon the Park with a view to showering his global largesse upon its struggling and deprived inhabitants.

By now, many readers will have seen the Rt.Hon. Robert GOODWILL’s email to a member of the public last September:

“Thank you very much indeed for your enthusiastic letter regarding York Potash.

I can tell you that York Potash have already received a large grant from the Regional Growth Fund to enable them to conduct research into processing of the polyhalite material which they hope to mine. I am absolutely determined to ensure that this project goes ahead and delivers the jobs that we so need in our area and at the same time, I hope that the environmental impact of this will be minimised and that knock on benefits to the community can be exploited.

Thank you very much indeed for your letter.

Yours sincerely”

That proviso “environmental impact of this will be minimised” seems already to have departed from the fundamental principles of the National Park & Access to the Countryside Acts, which promises zero environmental impact.

How many readers know that the grant to which Robert GOODWILL is referring amounted to £2.8 million?

One wonders how much Sirius Minerals has invested of its own $500 million capitalisation (that is to say, its shareholders’ money) in this York Potash project thus far. Of course, there have been overhead costs to cover; and a few salaries, the odd bursary, some glossy presentations and a carnival of test-drilling, and no doubt various other costly considerations. But then the share capital, too, was materialised out of a stream of hype, and anyway it’s only someone else’s money.

And how many know that Scarborough Borough Council has made an application to the Regional Growth Fund for £15 million in support of the York Potash project and that other manna-from-heaven windfall, the Dogger Bank wind-farm (no takers)?

It is in situations like this that one begins to recognise the deeper implications of the necessity for elected members and executive paid public servants to declare their interests.

How do you feel about a Council ‘insider’ who, having jumped in at, say, 12p is actually part of the decision-making process that determines how that glittering £15 million RGF grant is directed towards ‘bulling up’ the Sirius share prices? (Not that I am suggesting for one moment that anyone who would profiteer on his/her Broadband Allowance would stoop so low as to use the public purse as a ‘grow-bag’ for his/her own discreet investments).

Much of the talk on the various forums indicates that few of the Sirius supporters are concerned about whether or not the project ever comes on-stream. Nobody is speculating about how the dividends from the profits will underwrite their old-age. Everybody is talking about jacking the share prices as high as possible – and then bailing out with a handful of fast bucks before the latest incarnation of the South Sea Bubble bursts.

A good friend of mine tells me that when he jumped in at 12p, his ‘advisor’ recommended getting out completely at 38p. That remains his intention – always assuming that he does not get cold feet before the day. Forum chat suggests that 40p may be an optimistic ceiling unless the Secretary of State come up trumps for them. I am not suggesting for one moment that the Secretary of State jumped in at 12p, too!

There are those who argue, with some passion, that the region defined by the boundaries of the National Park is not having things so great at the moment:

- “The ‘financial down-turn’ has bitten hard”

- “The area needs this ‘shot in the arm’ in order to regenerate itself”

- “Our young people are bereft of any prospects the way things are”

They may not always disclose the extent and intensity of their own vested interest.

Nor can they point to an industrial development anywhere in the world, throughout two centuries, that was not the thin end of the wedge.

Those who argue that the North Yorkshire Moors has a long history of industrial exploitation and that potash mining is entirely in keeping are wittingly missing the point. Those industries pre-date the enlightened attitudes that resulted in the National Park & Access to the Countryside Acts.

Looking forward, I am not competent to evaluate the material passed to me just recently. The financial implications will need the eye of a corporate accountant, some of the technical papers appear to exist in more than one version, and the identities of most of the email correspondents are unknown to me; but the immediate impression that I form is that there are more than two sides playing this potash game, or share auction, or whatever it really is.

Those who dwell in the Park (and in Whitby), and who are enlightened enough to appreciate the sublime privilege of making our daily lives here – lives rich with meaning and emotion far beyond the trivial fluctuations of stock markets and pension plans – are immersed in a priceless and irreplaceable wonder of nature, and we are not ready to sell our birthright for a mess of potash*.

I leave you now with another pearl of wisdom from Sitting Bull, hero of the Little Big Horn:

“Only seven years ago we made a treaty by which we were assured that the buffalo country should be left to us forever. Now they threaten to take that from us also.”

Such is the thin end of the wedge.

So dig your potash if you must, Chris Frazer, but do it offshore, please. It may not be quite as profitable, but it would be much more considerate.

And leave the Park alone for the foreseeable future.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* “mess of pottage”

“A mess of pottage is something of little value for which something of great value is foolishly and carelessly exchanged, alluding to Esau’s sale of his birthright for a meal of lentil stew (“pottage”) in Genesis 25:29–34. The phrase connotes short-sightedness and misplaced priorities, the exchange of something immediately attractive for something more distant and perhaps less tangible but in the last analysis infinitely more valuable.”

![“Economical With The Truth?” [Part One]](https://nyenquirer.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/ROGUE_Council1-150x150.jpg)